Social housing is a key part of solving homelessness

Cancelling over 1500 new social housing builds is both fiscally and socially irresponsible, given homelessness is on the rise

The Minister for Housing, Chris Bishop, halted hundreds of Kāinga Ora housing developments across Aotearoa New Zealand. Public housing projects already in planning and ready to go were paused, reassessed, or cancelled; land previously earmarked for state homes will be sold. While Bishop frames this as “restoring financial discipline”, the reality is that dismantling public housing infrastructure is short-sighted and socially damaging. It also occurs within an environment where homelessness is rising faster than our population is growing.

Bernard Hickey reported the following:

Homelessness up 25% to 225% after motel clearances

Yesterday the Government finally released the Housing and Urban Development Ministry’s (HUD) Homelessness Insights report for June. It shows local outreach services, councils, Corrections, Health NZ and report rough sleeping has risen 25%-225% since the Government changed its policies to shut down emergency housing in motels and toughen its criteria for putting people into social housing.

HUD collated a variety of data more detailed and recent than from the 2023 Census, which found 4,965 people were sleeping rough or in cars, up from 3,624 in 2018, including that:

Auckland Council said outreach services found 809 people were sleeping rough at the end of May, up 89% from September 2024;

Tauranga Council said its call centre recorded reports of 619 homeless people in 2024, up 46% from 423 in 2023;

PARS Taranaki estimated the number of rough sleepers in Taranaki more than tripled to 35 in December 2024 from 10 in June 2024;

Porirua Council said its quarterly audits found the number of rough sleepers almost trebled to 18 by March 2025 from 7 in March 2024;

Whangārei District Council said public reports of homelessness rose 56% to 1,066 in 2024 from 680 in 2023, and it forecast 1,200 for 2025;

Wellington’s Downtown Community Ministry reported 328 homeless people in the March quarter of this year, up 5% from a year ago, while rough sleepers rose 24% to 141 in that period;

Christchurch City Mission report its outreach workers found 270 rough sleepers in the six months to March 2025, up 73% from 156 in the previous six months;

Corrections had reported at least 350 people who had just left prison had no fixed abode;

Hospital Emergency Departments reported 64 people had presented at EDs in the month of November 2024, up 88% from 34 in November 2023;

Health NZ reported homeless people had been forced to stay in hospital facilities for 954 total nights in the month of December 2024, up 42% from 669 in December 2023;

You can read more here:

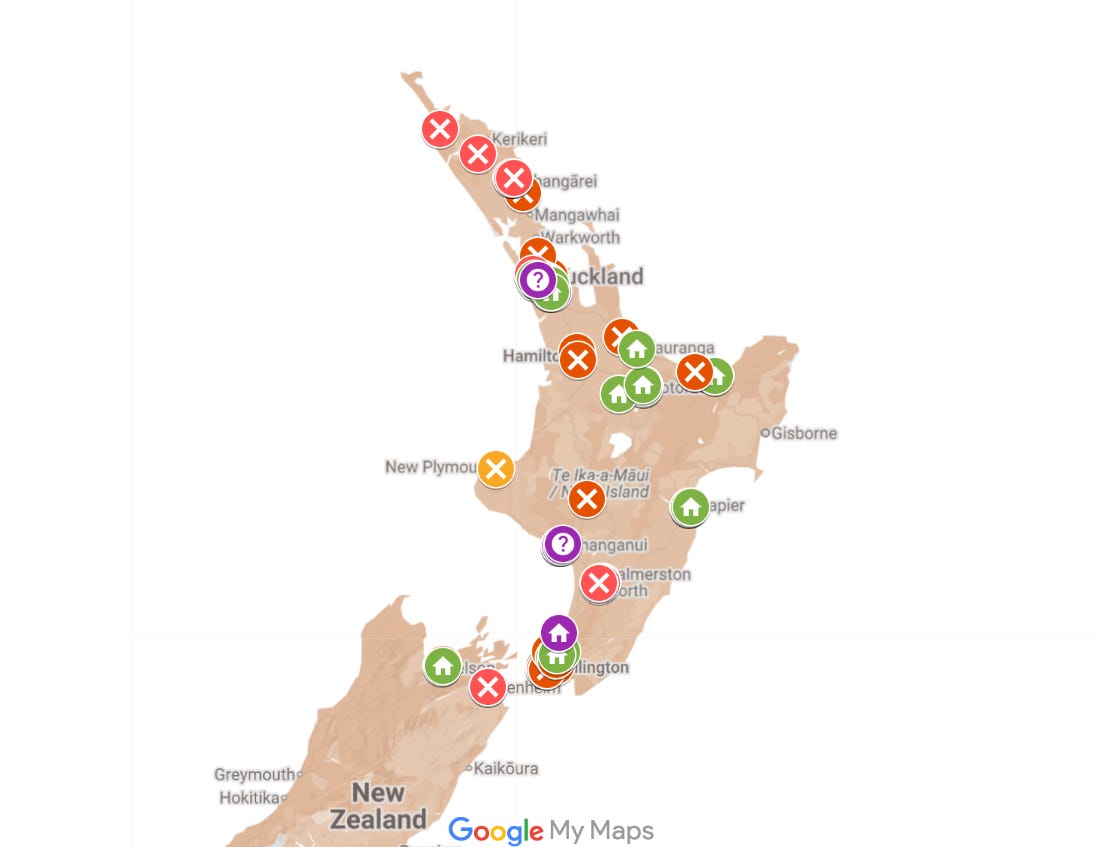

The cancelled social housing builds

Altogether 371 developments (involving 1,576 planned homes) have been cancelled by the Minister for Housing. Entire communities are impacted, from Ruakākā in Northland to Port Chalmers in Otago. Auckland, Hamilton, Rotorua, and Dunedin, have all seen major housing developments placed on hold. Flagship sustainable housing projects, such as Ngā Kāinga Anamata in Glendowie, have been abandoned. This is not a '“turnaround plan”; it is a large-scale rollback of public housing investment - investment that is much needed and would go some way to addressing the above homelessness statistics.

A quick list of the affected projects impacting on over 1500 new house builds and the consented projects that are now paused, cancelled, or reassessed:

Northland – 50-home development in Ruakākā halted; Kerikeri development shelved

Auckland – 185-home project in Onehunga reduced; flagship net-zero homes scrapped

Hamilton – 107 homes across two sites (incl. Endeavour Ave) on hold

Dunedin – 10 developments affected, including the Carroll Street redevelopment

Palmerston North, Wellington, Napier – multiple sites in limbo

Nationwide – 371 developments reassessed, affecting 1,576 homes

Full project list with sources here →

Action Station have also built a map of the paused public housing developments:

Cancelling already consented projects is fiscally irresponsible

Cancelling housing developments already underway is a waste of the work already undertaken; planning, design, site consultation, and infrastructure development will have already occurred across these sites. Halting these projects incurs sunk costs that will not be recovered. There are limited alternative sites available. Emergency and transitional accommodation are both more expensive to operate and less effective in meeting the needs of families.

The Minister for Housing describes cancelling these projects as ‘right-sizing’ Kāinga Ora. Despite his careful spin, the reality is that this is a deliberate de-prioritisation of public housing. In the midst of a housing crisis and defunded emergency and transitional services, no less.

This impacts on disabled people and families

More than a quarter of New Zealand households now rely on some form of housing support, from state homes to rent subsidies. One in four families cannot afford private market rents without government help.

The private market has failed to meet the accessibility related needs of disabled people and their families - so much so that there is a major shortage of privately-owned homes in Aotearoa New Zealand that meet basic accessibility standards (e.g., step-free entrances, wider doorways, accessible bathrooms), and even fewer that are fully accessible.

This has a flow-on impact for disabled people and their families, many of whom face systemic exclusion from the private housing market. Typically in Aotearoa New Zealand, it is Kainga Ora and associated community housing providers who incorporate universal design principles into new builds. Kainga Ora had a 15% goal for new builds to be fully accessible. Social housing projects being cancelled disproportionately harms disabled people and their families, including those with long-term health conditions, who are more likely to be living in adequate, damp, unhealthy, and inaccessible homes.

A lack of accessible housing forces many disabled people into unsafe, overcrowded, or institution-like settings. This is not by choice, but is a necessity, and further restricts autonomy, social participation, and employment. Accessible housing is a fundamental requirement for disabled people to live with dignity and independence in their communities.

A quick reminder of some existing quick stats around disability and housing:

Over 50% of disabled people live in rental accommodation, and at least half of those are living in poor quality rental homes.

Fewer than 2% of all NZ homes are estimated to meet minimum accessibility standards.

Disabled Māori and Pasifika are significantly more likely to experience overcrowding, dampness, and unaffordable rents.

Even though there is a high need for accessible social housing, the supply of purpose-built accessible homes remains critically low and is not projected to meet current need anytime soon.

In praise of social housing

There is a robust body of New Zealand-based research that provides strong evidence of social housing being a high-return social investment with significant flow-on benefits for the whole populace. Below I give an overview of the core benefits of providing stable, decent housing for individuals and families:

1. Stable social housing reduces crime.

Longitudinal research by the University of Otago found that youth offending dropped by over 10% amongst young people who moved into permanent social housing:

Three years after moving into public housing, alleged offences and court charges among young people reduced significantly – by 11.7 per cent and 10.9 per cent more than the general youth population. Rates of alleged offending and court charges also decreased among those receiving an accommodation supplement – 13 per cent and 8.6 per cent more than the general youth population.

The researchers undertaking the study have emphasized that secure housing supports school attendance, community bonds, and parental engagement, which are all key factors in lowering justice system interactions:

Dr. Yu says stable housing plays a crucial role in promoting social cohesion and reducing risk factors associated with youth offending.

"The security provided by guaranteed housing enables young people to more consistently attend school and establish strong community bonds, resulting in them being more engaged at school and better supported socially.

"Studies have also shown that having a stable home may lead to parents having more time to spend with their children, resulting in stronger parent–child bonds, and better emotional and physical well-being for the child."

Source: Phys Org

Stable housing provides a foundation for employment, whānau (re)connection, and for accessing support services, all of which are core elements that support positive, non-criminal, activities and engagement.

In addition to the above, another, separate study examined the outcomes of individuals released from prison. They found that individuals living in stable housing six months after release were 4.6 times less likely to be re-imprisoned than those with unstable housing (7% vs 34%). The authors concluded:

Our findings support addressing housing instability as an important factor in the cycle of reoffending and demonstrate an imperative to invest in comprehensive, long-term housing solutions for those leaving prison. Such housing solutions can be conducive to wider stability in life, the development of social capital and other factors associated with reduced recidivism and desistance from crime. Stable housing remains a fundamental pillar for sustainable and successful reintegration into society, and no person should leave prison with an unmet housing need.

2. Decent housing saves money in health

Comparative research tracking individuals moving from emergency housing to social housing shows significant improvements in health and wellbeing. Social housing residents benefit from improved environmental conditions (warm, dry, reduction in crowding), with flow on positive impacts for mental and physical health.

An evaluation of the Healthy Homes Initiative revealed that every $1 spent on creating warm dry homes delivered $5.07 in health savings. Over a period of five years, living in warm, dry, stable housing resulted in lowered hospitalisations (nearly 19% less), fewer emergency admissions, and reduced school absenteeism by 5%. Living in a warm, dry, stable home resulted in 10,000 averted hospitalisations - a significant cost saving for health.

Another study tracking transitions from emergency housing to social housing found a decrease in annual hospitalisation rates (0.50 to 0.29) and a decrease in the annual rates of mental health outpatient use (5.8 to 3.7) after people entered into social housing.

Poor housing conditions costs New Zealand taxpayers $141 million annually in avoidable healthcare costs and are linked to over 200 preventable deaths each year. Moving families into secure, affordable, stable homes could save the government $11 million over 15 years per 1,000 households. This saving includes reductions in healthcare and associated welfare costs.

3. Social housing results in improved educational outcomes

The Growing Up in New Zealand study shows housing instability significantly affects early cognitive development, school readiness, and continuity of education particularly in the first five years of life. Frequent residential moves and unstable housing in the first five years of a child’s life correlate with poorer cognitive development, reduced school readiness, and higher school transience. Housing instability too often leads to disrupted schooling and diminished readiness for learning.

Similarly, earlier evaluation research from the Housing Foundation and Tindall Foundation’s found that over 80% of residents who moved into stable, social housing reported improved wellbeing, with many parents noticing better school performance from their children.

The evidence is overwhelming: stable, affordable housing is foundational to improved education, health, and employment outcomes for young people. It is a crucial component of reducing crime, which has flow-on benefits to all of society. If the government is serious about addressing any of these issues, it must start by reversing their short-sighted cancellation of social housing builds and (re)commit to building homes for social and public good.

What can be done?

You know, I always like to include a range of options for responding. In part because having a meaningful action to undertake reduces that senses of helplessness that can occur. It also works as a reminder to all of us (myself included!) that we are not helpless in the face of callous decision-making, and that, despite it all, we still have the power to make a difference.

A non-exhaustive list of quick ways to respond:

Write to your local MP

Contact your local elected representative (Member of Parliament). Especially if you live in an area where housing projects have been cut. Share your views and ask them to publicly support the reinstatement of Kāinga Ora developments. You can find your MP and contact details here.

Attend local council/community board meetings

Local authorities can face pressure to rezone or sell public land, and often receive quite a few anti-social housing responses from NIMBYs. Let your local councillors know you support social housing! You can email them and also keep in touch with councillors to know when to attend local meetings and voice your support.

Raise awareness

Sharing stories, your thoughts, links to articles, etc on social media can help shift attitudes and opinions. It can also help you feel less alone! A solid rant can do wonders for relieving the angst. Posting in your local neighbourhood Facebook group is for the brave of heart indeed. Nonetheless, public support for social housing is much needed.

Sign up with Action Station

Follow this link to sign up and Action Station will be in contact with you to either link you up with an active campaign in your area, or to help you start one. You don't need to have any experience! And you will have support to start slow. You might just wish to run a digital petition, or perhaps to do more grassroots campaigning. This is what you can work out with Action Station, and you will have support all the way.

Vote in your local council and national government elections.

Ask candidates where they stand on social housing. Ask for a solid commitment to building social housing. Vote for those who advocate for evidence-based policy and investment in publicly owned social housing.

Thank you Dr Bex for another powerful article. You’ve laid it all out so clearly and with such care. I really appreciated how you back everything up with evidence and keep the focus on people at the heart of it.

You’ve also called out the spin and deflection from Ministers Bishop and Potaka, and from PM Luxon too for what it really is: cynical, short-sighted, cruel, and frankly disgraceful.

I loved your list of actions we can take at the end of your article.

🤔 I have had pause to think about the "accessibility" question on a personal level in recent times. 1) a relative who now needs a walker to get around - fortunate that the small private flat/house JUST has room to get through doorways inside 🤷 2) a visitor with a child in a largish push-chair couldn't get inside MY small house which made me think about IF I became unable to get around without a walker/wheelchair at some point, would I be able to modify my house (me and the bank own it!) OR would I have to find an accessible house, possibly somewhere away from my community etc 🤔 3) My area has major housing projects on formerly vacant land - by the bill boards it is private developers. The houses/units are all joined together like Coronation Street & front access is via 1 storey high stairs - and each unit is 2 or 3 storeys high - they don't look particularly high spec so unlikely they have elevator access from the rear (?) but it is closed off/private from rear courtyard so can't see (plus NO GARDENS or public common areas)

We are ALL one event away from needing accessible accomodation, so it is a no-brainer to ensure this is taken into account - with an ageing population even otherwise "well" people will need to be catered for either in rentals or their own existing homes.

As for the stats about the benefits of social housing, it is no longer speculative but as you outline it is well documented. Even without the research, a simple knowledge of humans we know or are ourselves, would predict that stable housing is a big plus to the human condition on every level. It is wilful blindness & a wish to keep the "wealthy & sorted" at the forefront of decisions, that drives this govt's approach to ignore what would be best for both individual citizens/families AND the country as a whole (health, crime, employment, community etc)