Child disability data and life outcomes

Fund families in ways that work for them.

When disabled children and their families can access the services and support they need, they thrive across their life course.

When governments and societies fail to provide needed services and supports, then it shows up in statistics and life outcomes, like the following:

Disabled children and health

The 2022/2023 NZ Health Survey gives a snapshot of what is happening for disabled children (compared with non-disabled children):

Mental health: Disabled children are almost five times as likely to have consulted with a psychologist, counsellor, or psychotherapist about mental health in the last 12 months as non-disabled children (12% vs 3%).

Emotional, behavioural and social challenges: Disabled children are almost 10 times as likely to experience emotional and/or behavioural challenges than non-disabled children (39% vs 4%). Disabled children are over three times as likely to experience issues with peers when compared with non-disabled children (33% vs 10%).

Parenting: Parents of disabled children are 15 times as likely to report not coping (13% vs 1%) compared with parents of non-disabled children.

Food insecurity: Disabled children are almost three times as likely to experience food running out often (11% vs 4%), and more than twice as likely to be in households that use food grants often/sometimes.

Disabled children and education

Te Ihuwaka, in partnership with the Office for Disability Issues and the Human Rights Commission, has found that education across NZ schools and early childhood services is failing disabled learners. For example:

disabled learners are being discouraged from enrolling in schools and services

disabled learners are more likely to be stood down

one in five parents have been discouraged from enrolling their disabled child at a local school (one in four for early childhood)

a quarter of parents have been asked to keep their disabled child home from school

Additionally, disabled learners reported feeling excluded from school activities, and the research found their sense of belonging declines as they progress through education - with almost a third of disabled learners saying they do not feel they belong at school.

Disabled youth in education, employment and training

In the June 2017 quarter, 42.3% of disabled youth aged 15–24 years were not in employment, education, or training (NEET) - Statistics NZ

NEET rate for disabled youth (42.3%) was over four times that of non-disabled youth (10%).

Only one-third of disabled youth participated in the labour force.

Disabled youth were more likely than non-disabled youth to have no qualifications.

NEET: Not in employment, education, or training

NILF: Not in labour force

Error bars represent variability in estimates.

Disabled adults in employment

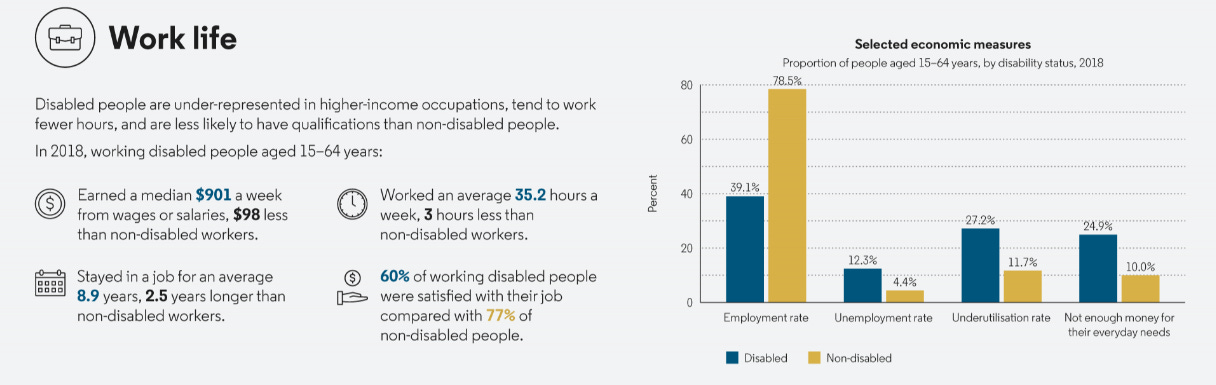

The disability gap 2018: Disabled people are under-represented in higher-income occupations, tend to work fewer hours, and are less likely to have qualifications than non-disabled people.

In 2018, working disabled people aged 15–64 years:

Earned a median $901 a week from wages or salaries, $98 less than non-disabled workers.

Worked an average 35.2 hours a week, 3 hours less than non-disabled workers.

Stayed in a job for an average 8.9 years, 2.5 years longer than non-disabled workers.

60% of working disabled people were satisfied with their job compared with 77% of non-disabled people.

We can do better

Looking across the life course, the statistics listed above are not inevitable. The provision of flexible disability support funding, ensuring we build accessible homes and workplaces, allowing for tailored/individualized support, providing ongoing training for non-disabled people - all of these contribute into positive life outcomes for disabled people and their families.

Readers, you may notice that Whaikaha - Ministry of Disabled People, has limited involvement in the outcomes listed above. Responsibility for the above statistics also lies with Ministries such as Health, Education, MBIE, Social Development, and the like. All of our social institutions and governing bodies have the ability to contribute and make a difference when it comes to disability outcomes.

Aotearoa New Zealand is a wealthy country; we can and should do better in terms of ensuring positive outcomes across the life course of our populace.

So sad to read those statistics but thank you for the work in collating them. And a big ‘hear, hear’ to your point about other Ministries also needing to meet their responsibilities