Alcohol is no solution for what ails us

CW: Suicide, mental health, alcohol

This week I was utterly floored to hear a leader of a nationally recognisable mental health organisation claim the following, on national radio no less:

"Alcohol is not a problem for people with mental health issues. It's actually the solution to our problem, until you come up with a better solution … I would suggest to you that alcohol has prevented more young people from taking their own lives than it actually takes their own lives."

They have since doubled down on their statements, even going so far as to summarize research (primarily undertaken in the 70’s and 80’s) supporting their claims on their LinkedIn.

The thing is, though, research published at the start of this century is now over two decades old - and fast becoming out of date. Research from the 70’s is over 50 years old. Psychology, as a discipline, moves and grows and develops. Ideas change. Theories evolve. Our understanding of complex societal issues shifts and deepens.

When you undertake professional training, and even more so if this includes completion of a post-graduate research degree, you literally learn how to “do your own research”. Proper research. Not just a google session or a trawl through the internet. Proper, actual research that considers the robustness and validity of academic publications. You delve into components such as methods used, participants, recruitment methods, sample size, questions asked, statistical measures, and so on.

You also learn how to synthesize published, peer-reviewed work, how to run a critical eye over it and consider who funded the work and why, what the implications are, where the gaps and holes exist. You learn that being published in a peer-reviewed, high-impact academic journal is no guarantee that the research is sound, or that it continues to hold validity twenty years later.

A meta-analysis is a type of study that takes a broad sweeping look across the published, peer-reviewed literature to determine key trends. It goes beyond simplistic one-off findings and considers what the data is telling us across a wider range of studies. A meta-analysis shakes the studies out, pokes holes in their findings, and checks the research robustness.

A 2021 meta-analysis of 33 studies found that alcohol use was associated with a 94% increased risk of death by suicide. I’m saying that again:

alcohol use associated with a 94% increased risk of death by suicide

That is sobering figure indeed (pun intended, sorry).

The authors of the study also found a stronger alcohol use-suicide link for women, and that heavier alcohol use is more problematic for women's health.

There is nothing in this study to indicate any empirical support whatsoever for claims of alcohol being a solution or a useful suicide prevention tool. What it does show is a clear link between alcohol use and harm.

What do we know about alcohol use in New Zealand?

The most recent Ministry of Health data (meticulously gathered, checked, analysed, and published June 2024) regarding Mental Health and Problematic Substance Use found that, while there was a decrease in moderate-high problematic alcohol use, this only occurred for men - the prevalence of moderate-high problematic alcohol use for women has remained relatively stable.

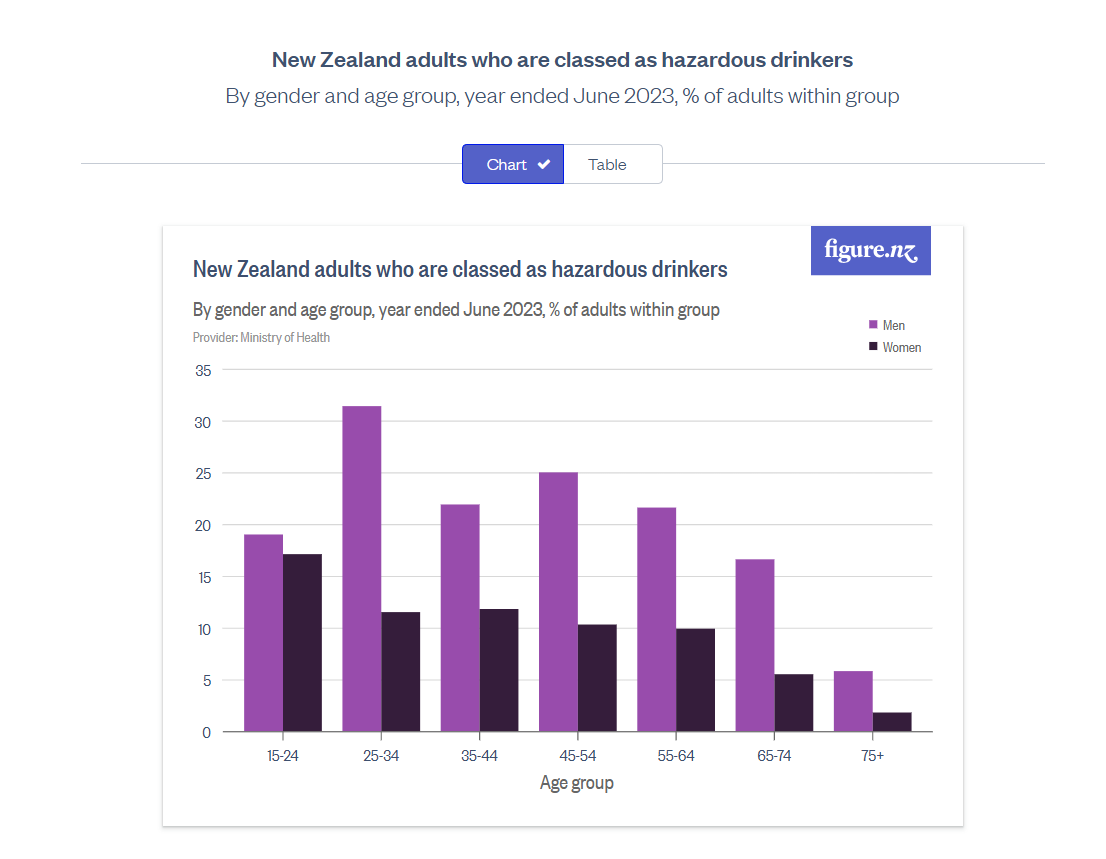

Figures NZ made a lovely wee graph of hazardous drinking in New Zealand from the data set:

The data showed that women had poorer mental health, and increasing incidence and severity of anxiety and/or depression.

The data also showed that at risk population groups are more likely to experience anxiety and/or depression symptoms and more likely to engage in problematic substance use. That is, there is a clear correlation between poor mental health and heavy drinking, although it isn’t entirely clear how the two influence each other.

We use alcohol a lot in New Zealand, as a social lubricant, for stress relief, to cope with everyday life. It's normalised. But it's not healthy, and it's especially not healthy for women, for either our mental or physical health.

If we take the finding from the meta-analysis and consider the implications for the data from the Ministry of Health, it is reasonable to conclude that alcohol use in New Zealand is a driver of poor mental health and results in increased incidence and severity of both anxiety and depression.

One might even go so far as to consider that New Zealanders across all age groups drink alcohol as a solution instead of seeking help with their mental health.

Alcohol causes harm to New Zealand youth especially

A New Zealand based study (published 2023) evaluated and ranked drug harms using a multi-criteria decision analysis framework. The authors considered harm both within the total population and amongst youth. They found that alcohol related harm far outstripped that of other drugs:

Young people are also harmed by alcohol (mis)use; binge drinking remains high by international standards and is associated with increased self-reported harm. The graph from Crossin et al’s analysis below shows the harm caused by alcohol and other drugs across a range of areas:

The issue of alcohol (mis)use in New Zealand is widespread, and there remains political reluctance to implement evidence-based meaningful steps to reduce alcohol-related harm (increasing the price of alcohol via excise tax; eliminating alcohol advertising and sponsorship; reducing the density and opening hours of alcohol outlets; and increasing the age of purchase from 18 to 20; recommendations from the New Zealand Law Commission, 2010).

Claiming on a national platform that alcohol use is "not a problem" and that alcohol use is "the solution...until you come up with a better solution" when New Zealand has a national problem with both help-seeking and alcohol use is unfortunate, unhelpful, and does little to encourage people to find the help they need. It also plays into the hands of the alcohol industry, who very cleverly target consumers (especially women) in highly sophisticated ways.

(Read The Wine O-Clock Myth for more on the damage alcohol is causing to women: physically, emotionally and socially; and the potential reasons why so many women are drinking at harmful levels)

Having a solid rant with friends over a backyard barbie is one thing; making verifiably inaccurate public statements on national radio, print media, and on social media platforms is quite another. Our collective mental health deserves better than thoughtless, sulky comments by someone who didn’t get a liquor license for a fundraiser.

.

Good call. I know Mike, I like Mike, but this isn't okay - he simply isn't qualified for this. It's irresponsible all round and unfortunately endorsed by this current govt who operate on what their mates say in private, their own reckons and disregard actual evidence. Not Mikes fault necessarily - he's perfectly illustrated what happens when unqualified people are given authority

Unfortunately what New Zealand has is a crass government who say one thing then enact a completely different agenda. Any one with half an ounce of common sense would understand that a man who by his own admission suffers from alcoholism and the 'black dog' of depression is exactly the last person we need heading up such an important issue as mental health awareness and funding priorities. These are very strange days, where the 'post truth' era seems to allow any fool locking academic qualificationsl, political nouse, inellectial rigour or just basic common sense to call themselves experts in whichever feild represents their hobby horse of personal focus. Goodness alone knows where it all ends, but nothing good will be an outcome as sure as day follows night