ADHD statistics show we continue to fail our young people

A post for neurodiversity week

This week is neurodiversity week!

Yesterday, I shared Jessica’s personal stories of living with ADHD.

Today, I am posting on the intersection of policing and disability, with a focus on those being policed. In doing so I pull out some startling statistics about young people, policing, and ADHD. Do persevere with reading the post - or scroll to the end if you only want the ADHD stats.

At the end of 2024, the Donald Beasley Institute published their findings on a project titled Understanding Policing Delivery: Tākata Whaikaha, D/deaf and Disabled People.

This report is a standalone study and represents a small part of the Understanding Policing Delivery research project. It focuses on the perspectives of Police-experienced tākata whaikaha, D/deaf, and disabled people, as well as that of Police Officers. In doing so, the researchers have generated useful evidence for informing, transforming, and strengthening relationships between Police and the disability community.

The findings are interesting, as they reflect wider societal attitudes towards disability:

Essentially, the Police, like many others in our society, cannot differentiate between disability-related behaviour and criminal actions. This leads to Police laying more serious charges than they otherwise would, not treating disabled people seriously, and escalating the use of force more than they would otherwise:

Some of this is related to a lack of understanding about disability, a lack of knowledge on how to de-escalate situations with disabled persons (as this requires a different approach to dealing with non-disabled), and increased risk to the disabled person:

Many of these observations, experiences, and suggestions for interacting with disabled persons are applicable beyond policing. Teaching, for example, and parenting, are other authority figures where adopting a compassionate, relational approach results in far better outcomes for all involved, but especially the young person.

This becomes incredibly obvious when managing ADHD.

ADHD and the criminal justice system

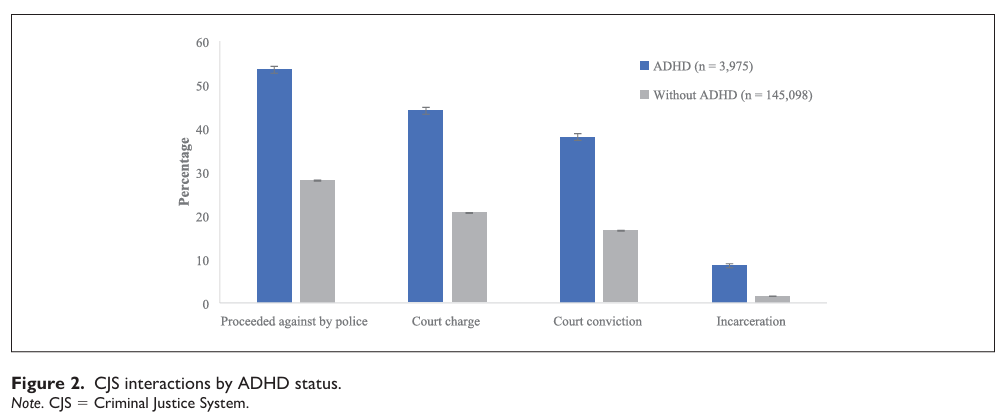

One of the authors of the DBI report was involved in a deep dive into ADHD and policing statistics in Aotearoa New Zealand. Their findings were shocking:

OVER HALF of young adults with ADHD had interacted with the criminal justice system by their 25th birthday

Individuals with ADHD were over TWICE as likely to be proceeded against by police and charged or convicted in court

Young adults with ADHD were almost FIVE TIMES as likely to be incarcerated than those without ADHD.

Essentially, if a young person has ADHD they are more likely to be prosecuted by police, more likely to be charged or convicted in court, more likely to be convicted, and more likely to be incarcerated. This risk increases as individuals with ADHD proceed through the criminal justice system.

The study was a statistical deep dive, so we don’t know exactly why there is such disparity.

We can make some guesses based on existing literature:

Impulsive-type ADHD may mean the young person engages in more impulsive (and more violent) crimes (Fletcher & Wolfe, 2009)

There may be a relationship between ADHD and reactive aggression - think about oppositional defiance disorder or conduct disorder or similar type behaviours which are often associated with ADHD (Erskine et al., 2016)

ADHD can lead to reactive aggression in response to conflict or perceived provocation (Retz & Rösler, 2009)

Alongside this published literature on ADHD, the 2023 Household Disability Survey found the following:

3 out of 5 disabled people had unmet needs

over half of disabled children had an unmet need for support or accommodations at school (48,000 children)

While the survey doesn’t break these figures down by disability type, it does give us some indication of the level of unmet need for disabled people, including neurodiverse persons.

We also know that in Aotearoa New Zealand, access to psychologists and psychiatrists for an ADHD diagnosis and/or associated medications has become nigh on impossible through the public system. The cost of going private puts access to a diagnosis and subsequent supports out of reach for many.

If we think about the 2023 Household Disability Survey results, the barriers to accessing diagnosis and support, and the DBI report into policing, we can see that we are failing our young people.

There is a strong need for ADHD specific skills and training for teachers, police, and parents so that they can successfully de-escalate situations with young people with ADHD.

There is a desperate need for a publicly funded pathway into diagnosis and support, including (but not limited to) medication and therapeutic techniques.

If we have $39million for military academies, we absolutely have money to upskill teachers, police, parents, and others regarding supporting individuals with ADHD.

If the Minister for Mental Health can shift funds on a whim to his pet projects, we absolutely can fund psychologists and psychiatrists to better meet the needs of individuals with ADHD.

These grim statistics don’t have to be the future for our young persons with ADHD. We can and we must do better.

References:

Anns, F., D'Souza, S., MacCormick, C., Mirfin-Veitch, B., Clasby, B., Hughes, N., … Bowden, N. (2023). Risk of criminal justice system interactions in young adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Findings from a national birth cohort. Journal of Attention Disorders, 27(12), 1332-1342. doi: 10.1177/10870547231177469

Donald Beasley Institute. (2024). Understanding Policing Delivery: Tākata Whaikaha, D/deaf, and Disabled People. New Zealand Police.

Erskine, H. E., Norman, R. E., Ferrari, A. J., Chan, G. C. K., Copeland, W. E., Whiteford, H. A., & Scott, J. G. (2016). Long-term outcomes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(10), 841–850. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.06.016

Fletcher, J., & Wolfe, B. (2009). Long-term consequences of childhood ADHD on criminal activities. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 12(3), 119–138.

Retz, W., & Rösler, M. (2009). The relation of ADHD and vio lent aggression: What can we learn from epidemiological and genetic studies? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 32(4), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.04.006

Your posts are so informative. Thank you. I'm learning so much. Got my diagnosis yesterday, so will be navigating my way to understanding more about AuDHD.

🫂 Makes total sense that lack of understanding & appropriate training would lead to behaviour being misinterpreted 😵💫 Hell I'm neuro-diverse & don't understand myself sometimes 🤷🏻♀️but much clearer once I knew what the cause was, & learned strategies and/or accepted that is "who I am"

But seriously - the main answer is diagnosis & adequate support so less conflict with Police in the first instance when often it will be a high pressure situation & little time for deciding the diagnosis when dealing with an unknown "offender" by an officer attending. Then good training & systems should stop the subsequent higher charging rate & more serious charges ⁉️

If only someone, I don't know, an adequately funded education & health sector, could train enough people in all the systems neuro-diverse people (in this case ADHD) will encounter so BOTH parties can navigate through with minimal misunderstanding and/or harm 🤷🏻♀️